Anatomy of a MAGA Argument

Why so many fallacies are hiding in plain sight—and how to spot them before they spread

If you’ve ever engaged with MAGA commentary online, chances are you’ve encountered a logical fallacy—or five.

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that, at best, weaken an argument and, at worst, render it completely invalid.

While fallacies appear across the political spectrum, MAGA-aligned arguments frequently depend on them. These arguments tend to emphasize emotion over logic, tribal loyalty over reflection, and the repetition of popular slogans.

Research backs this up. A 2024 study found that Trump leaned heavily on fallacies during debates; ad hominem attacks surged in MAGA-aligned online posts after 2016; and conservative rhetoric more often favors metaphor and emotional appeal over evidence-based reasoning.

My goal here isn’t just to expose flawed arguments. It’s to help all of us—myself included—recognize the ways faulty logic creeps into our thinking, and to move toward conversations rooted in clarity, honesty, and curiosity.

Let’s take a scalpel to this commonly used MAGA argument below. Inside, you’ll find a skeleton made of false equivalency, strawman, whataboutism, misleading statistics/cherry-picking, implied causation, and appeal to ridicule.

Today I swung my front door wide open and placed my Remington 30.06 on the deck rail. I left six cartridges beside it, then left it alone and went about my business. While I was gone, the mailman delivered my mail, my neighbor across the street mowed his lawn, a girl walked her dog down the street, and quite a few cars stopped at the stop sign near the front of my house. After about an hour, I checked on the gun. It was still sitting there, right where I had left it. It hadn't moved itself off the deck rail. It hadn't killed anyone, even with the numerous opportunities it had presented to do so. In fact, it hadn't even loaded itself. You can imagine my surprise, with all the hype by the Left and the Media about how dangerous guns are and how they kill people.1 Either the media is wrong or I'm in possession of the laziest gun in the world.2 The United States is third in murders throughout the World. But if you take out just four cities: Chicago, Detroit, Washington DC and New Orleans, the United States is fourth from the bottom, in the entire world, for murders.3 These four Cities also have the toughest Gun Control Laws in the U.S.4 All four of these cities are CONTROLLED BY DEMOCRATS. It would be absurd to draw any conclusions from this data - correct? Well, I'm off to check on my spoons. I hear they're making people fat .5

1. Strawman

It hadn’t killed anyone, even with the numerous opportunities it had presented to do so. In fact, it hadn’t even loaded itself. You can imagine my surprise, with all the hype by the Left and the Media about how dangerous guns are and how they kill people.

In this example, the speaker distorts the opposing argument by suggesting that people believe guns load and fire themselves—an absurdity no one is actually claiming. By referencing “the Left” and “the Media,” the post uses mockery to shut down a real conversation about public safety.

2. Appeal to Ridicule

Either the media is wrong or I’m in possession of the laziest gun in the world.

While humor can defuse tension, this isn’t that. It’s mockery posing as insight—a tactic used to dismiss, not engage.

3. Cherry-Picking/Misleading Statistics

But if you take out just four cities: Chicago, Detroit, Washington, DC and New Orleans, the United States is fourth from the bottom, in the entire world, for murders.

Even if we humor this claim and remove those four cities, we’d still see tens of thousands of murders annually. The U.S. would remain near the top globally.

Beyond the flawed math, the logic itself collapses. You can’t remove major cities from a national average and call the result representative. It feels like a strong argument because it confirms a belief—but confirmation is not truth. If we want our positions to be rooted in reality, we have to check claims, examine context, and ask hard questions.

4. Implied Causation

These four Cities also have the toughest Gun Control Laws in the U.S.

This statement implies that strict gun laws cause high murder rates. But correlation is not causation. Without considering factors like poverty, systemic inequality, and historical policing practices, we miss the bigger picture—and that means we miss real solutions, too.

5. Whataboutism

Well, I'm off to check on my spoons. I hear they're making people fat.

Instead of addressing the concern, the speaker uses a false analogy—spoons and obesity—to mock and deflect.

These fallacies might look like strong arguments at first glance, but with further discernment, they tarnish truth, get in the way of real understanding, and make it harder to solve problems.

Fallacy Field Guide: A Quick Reference for Spotting Rhetorical Sleight of Hand

Fallacies appear across the political spectrum, but this guide focuses on patterns especially common in MAGA-aligned rhetoric, which is the subject of this piece.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, but it includes some of the most frequent fallacies found in today’s political discourse—particularly online.

Ad hominem:

Attacking the person making the argument instead of engaging with the argument itself.

Example: “You’re just a libtard who hates America, so nothing you say matters.”

This doesn’t address the issue. It shuts down dialogue by turning disagreement into personal insult.

Straw Man:

Misrepresenting someone’s position to make it easier to attack.

Example: “By demanding due process for undocumented immigrants, you're really saying you want criminals to stay.”

That’s not what due process advocates ask—it’s a demand that people be treated fairly under the law. The rhetoric is twisted into a claim no one actually makes, making it easier to dismiss concerns about justice and rights.

False dilemma:

Presenting only two options when more exist—usually one extreme and one unacceptable.

Example: “Either you support Trump, or you hate America.”

This fallacy creates a black-and-white scenario where there’s actually nuance. It oversimplifies complex issues to pressure people into one narrow choice.

False equivalence:

Comparing two things as if they’re morally or logically the same—when they’re not.

Example: “If guns kill people, then spoons make people fat.”

Guns are designed to kill. Spoons are not. This oversimplifies the issue to avoid real accountability.

Slippery slope:

Arguing that one action will inevitably lead to a chain of extreme or disastrous consequences.

Example: “If Kamala Harris were elected, we’d be in World War III by now.”

This kind of claim skips evidence and jumps straight to fear—relying on worst-case scenarios built on hypotheticals.

Whataboutism:

Responding to criticism by deflecting to someone else’s wrongdoing—real or imagined.

Example: “You’re upset about Trump’s lies? What about Hillary’s emails?”

This doesn’t justify the behavior in question—it just changes the subject. It’s not an argument; it’s a distraction.

Red herring:

Bringing up an unrelated issue to distract from the topic at hand.

Example: “Why are we still talking about January 6? The real problem is inflation.”

This shifts the conversation away from accountability to a completely different (though emotionally charged) topic. It doesn’t refute the original issue—it just avoids it.

Appeal to ignorance:

Claiming something must be true simply because it hasn’t been proven false.

Example: “No one’s proven the protestors aren’t paid by George Soros.”

This fallacy relies on the absence of disproof to make a claim seem credible. But a lack of evidence against something isn’t the same as proof that it’s happening.

Moral Equivalence

Suggesting that two actions are equally wrong (or right), even when the moral weight is vastly different.

Example: “Both sides riot—January 6 was no worse than the BLM protests.”

This ignores key differences in scale, motive, and context. Equating them morally oversimplifies the issue and downplays real harm.

Reading Critically in a Biased World

When evaluating a news source, two things matter most: reliability and bias. Every journalist and outlet brings some bias to the table—that’s human. But we can still aim for clarity.

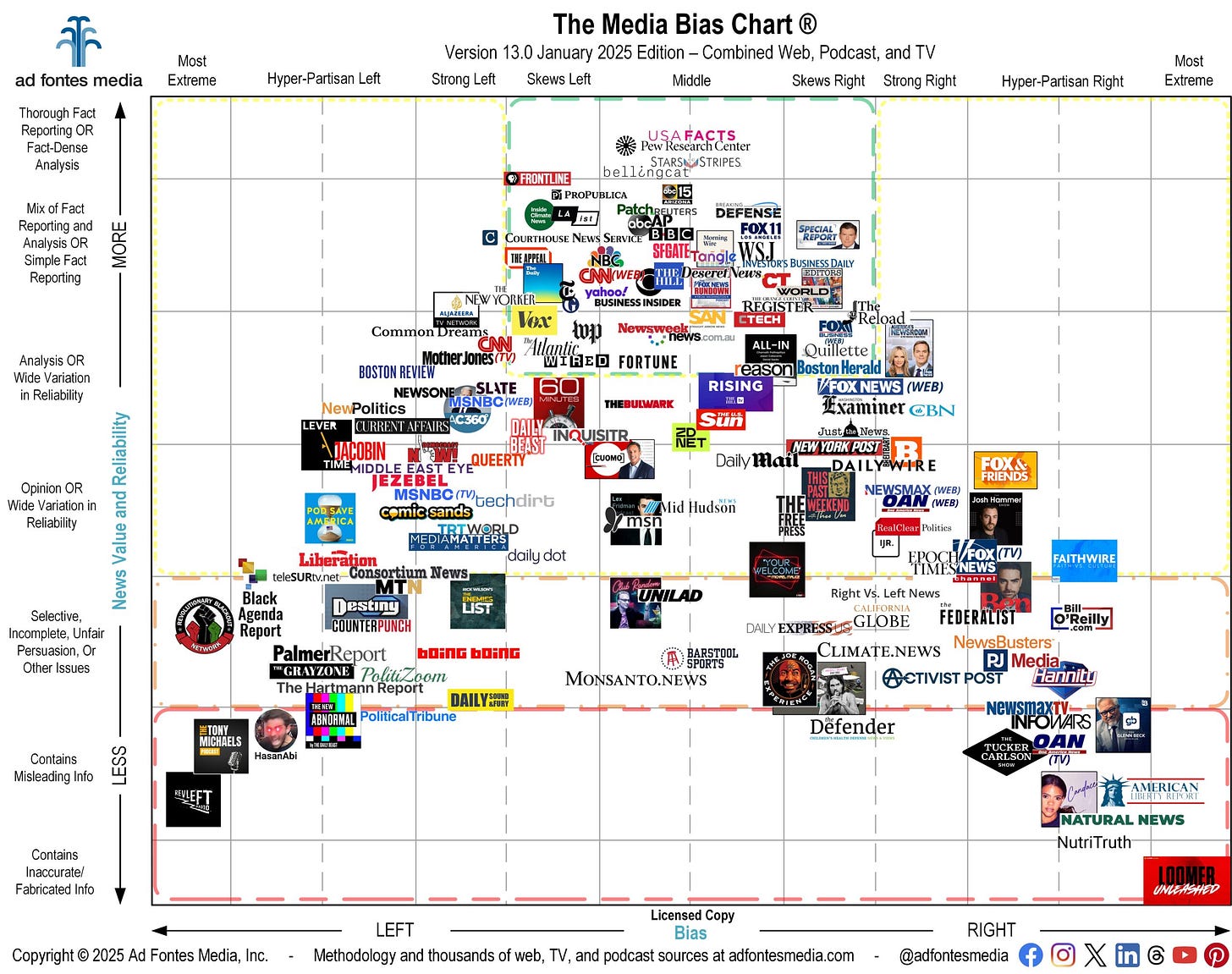

Three helpful tools for assessing media bias and reliability are Ad Fontes, Ground News, and AllSides. All three offer ways to check whether the information we're consuming is trustworthy—and whether we’re only hearing one side of the story.

Ad Fontes

Ad Fontes brings together analysts from across the political spectrum who review sources and apply a consistent methodology to rate their reliability and bias.

Their Media Bias Chart is especially helpful for quickly assessing the reliability and political lean of a specific outlet.

Source: Ad Fontes Media Bias Chart, Version 13.0 (2025). Used under fair use for educational and commentary purposes.

Ground News

Ground News illustrates the skew of bias: right, left, or center. It also presents the reliability of several articles from different outlets related to the same topic. Readers can then compare the different spin presented by news sources depending upon their bias. It even includes “Blindspot” alerts showing stories one side ignores.

A recent headline on Ground News relates to the military parade for the Army’s 250th anniversary. Here is a summary of how left-leaning and right-leaning outlets differed in coverage:

“Left-Leaning outlets frame the Army’s 250th anniversary parade primarily as an extension of Trump’s alleged authoritarianism, using terms like ‘militarization’ and highlighting the parade’s timing on Trump’s birthday to cast it as politically charged, while emphasizing nationwide ‘No Kings’ protests as a principled rejection of authoritarianism and wasteful spending amid social budget cuts.”

“In contrast, right-leaning coverage celebrates the parade with patriotic and valorizing language—'honors,’ ‘might,’ ‘patriotic pride’—portraying it as a necessary display of military strength and Trump’s respect for the armed forces, dismissing protests as ‘baseless accusations.’ These starkly divergent rhetorical tones reveal a core ideological divide centered on perceptions of military symbolism and Trump’s legacy, even as both sides agree on parade facts like troop numbers and the event’s historic scale.”

AllSides

AllSides shows how the same news story is covered by left-, center-, and right-leaning outlets side by side. This makes it easy to spot differences in framing, tone, and even what details get emphasized or ignored. It’s a useful tool for breaking out of an echo chamber and seeing how bias shapes not just what’s said, but how it’s said.

If you're looking for the most accurate information, start with center-based sources that score high in reliability. Does this mean you can’t read sources that are right- or left-leaning? No. In fact, reading across the political spectrum can help us stay open to other perspectives and be more aware of how others see the world.

Whatever you’re reading, stay curious, think critically, and ask how bias might be shaping the message.

It’s tempting to read a claim that confirms what we already believe and immediately hit “share.” It feels good to have our worldview validated—but feeling right and being right aren’t the same thing.

If we’re serious about building arguments on truth—not just tribal affirmation—we have to pause, ask questions, check sources, and resist the urge to repost just because it gives us that emotional hit.

At its best, an argument isn’t about winning—it’s about learning.

Somewhere along the way, we lost sight of that. Social media turned disagreement into performance. Political rhetoric turned persuasion into combat. But the goal of a good argument isn't to defeat your opponent—it’s to understand the issue more deeply, to test your own views, and maybe, just maybe, to grow.

That’s why logical fallacies are so harmful: they don’t just weaken arguments—they short-circuit dialogue before it has a chance to become meaningful.

In past generations, students were often taught how to argue. Not in the sense of yelling, but in the form of structured debate—where you were graded not on whether you “won,” but on how clearly you understood your position and how respectfully you responded to the other side.

Today, that’s becoming rare. Participation in high school debate has dropped in many districts, and some students graduate without ever learning how to evaluate an argument, spot a fallacy, or separate emotion from logic. For decades, school debate programs gave students a practical space to learn how to argue effectively—not to ‘win,’ but to learn. That changed rapidly: participation fell from over 10,500 policy debaters in 2018–19 to just over 7,000 by 2020–21—a 44% drop in two years.

As fewer young people learn how to build, analyze, or deconstruct arguments, we all become more vulnerable to rhetorical chaos. It’s no wonder our national conversations have devolved into memes, insults, and bad-faith distractions.

The viral post dissected in this piece reflects what many MAGA-aligned arguments rely on: a carefully packaged illusion of common sense that falls apart under scrutiny. It feels like logic. It sounds like reason. But it’s designed to distract, dismiss, and deflect.

When we peel back the skin of rhetoric designed to provoke rather than persuade, we find the bones of bad logic. If we want a healthier democracy, we have to start with the diagnosis—and the courage to face it.

What are some examples of logical fallacies you have seen recently? Let me know in the comments!

I welcome thoughtful disagreement, but I ask that comments be rooted in facts, not slogans.

If this resonated with you, I hope you’ll consider subscribing or sharing. If you’re still reading, thank you. It means you’re thinking. And that matters.

Sources

(PDF) Fallacy as a Strategy of Argumentation in Political Debates

Computational analysis of US Congressional speeches reveals a shift from evidence to intuition

National Circuit High School Policy Debate Participation is Cratering

Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, Third Edition. University of Chicago Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0-226-41129-3.

If I could I would like this a million times! This is so informative and helpful! Oftentimes when I’m trying to explain something I find wrong in these arguments or even my own in self-reflection, I don’t really know what to say or how to describe my critiques. Learning to recognize these fallacies I feel can also assist our critical thinking and aid diplomatic and productive discussions. Thank you so much for this article!!